My I urge, then, first of all, that petitions, prayers, intercession and thanksgiving be made for all people - for kings and all those in authority, that we may live peaceful and quiet lives in all godliness and holiness. This is good, and pleases God our Saviour, who wants all people to be saved and to come to a knowledge of the truth.

1 Timothy 2:1 - 3

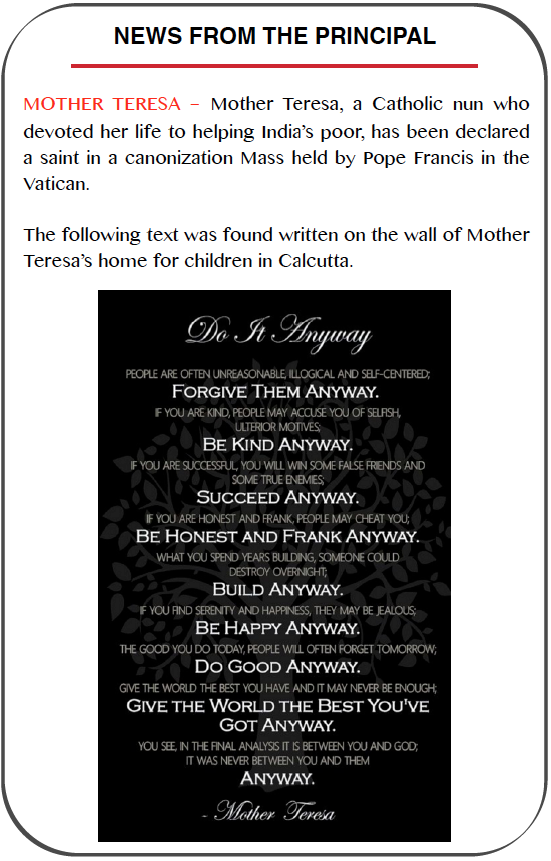

As Catholic schools we should not be ashamed of our mission to encourage and grow to holiness. The call to holiness (and wholeness) is made to all Christians. But what is holiness, and why is it so important? Holiness is derived from God as an expression of his extraordinary and immense goodness. As believers we participate in this holiness through our experience of God’s presence in our lives. We do not automatically share in that holiness: each of us must respond to the call, grow in awareness of God’s presence, express it through gratitude, humility, love and justice for others. This doesn’t make us holy, it means we gain a share, a space, a place in God’s holiness.

Holiness is important because it permits and resources our capacity to live full and rich lives (wholeness – they’re intimately related).

So, what does holiness look like? We have certainly seen it in the lives of St Teresa of Kolkata, St John Paul (II), St John (XXIII) and surely in the life of the Dalai Lama. But they are very religious. I’m reasonably sure, however, that religious people do not have a stranglehold on holiness. For gratitude, humility, love and justice for others are experienced and expressed by so many about us. I have been privileged in my life in having met a raft of ‘holy’ people – bishops, priests, religious brothers and sisters, but most have been people like you. Yet when I see the devotion of wives for their husbands, fathers for their children, grandparents for their grandchildren, friends for one another, I see quite clearly how God’s holiness overflows into their lives and it is quite awe inspiring.

Coming to recognise God’s role in this generous giving is what our job in Catholic education is. In Paul’s letter to Timothy (6:11-16) we are asked to be ‘filled with faith and love, (be) patient and gentle’ – that is, we must seek to be holy.

What this means on a day-to-day basis will be entirely dependent upon your gifts and capacity. In some instances it may mean offering your every living moment to others through a life of contemplative prayer, or being a nurse, a teacher, a emergency services worker, office worker, stay at home mum or dad.

We must ‘fight the good fight with all our might’ so that the daily grind itself does not become our reason for living, the fight is to ensure we can see our wholeness being unfolded in word and action. Wherever we are in our lives that is where our holiness, our place and space with God lies.

Peter Douglas

HEAD OF SCHOOL SERVICES, NORTH

God's joy

America Magazine/August 29-September 6, 2016 Issue [2]

John W. Martens

“Against you, you alone, have I sinned, and done what is evil in your sight” (Ps 51:4)

I hate sin. Not enough to stop doing it, try as I might, but I truly hate it. The older I get, the more I recognize sin as persistent foolishness, darkness and nothingness that pulls me away from God, whispers false promises in my ears about new pleasures, asks, “Why not?” or assures me, “You deserve it!” With the purported author of Psalm 51, King David, I can say with honesty that “I know my transgressions, and my sin is ever before me.” And I know now, with the psalmist, that “against you, you alone, have I sinned, and done what is evil in your sight” because every sin against another of God’s creatures or God’s creation is an act that draws me away from God’s love and the joy that God has prepared for me.

I might not be the foremost sinner. The author of 1 Timothy, traditionally ascribed to the apostle Paul, claims that title, saying that he “was formerly a blasphemer, a persecutor, and a man of violence” and, indeed, “first” among sinners. But that’s the point, is it not? When we are caught up in sin, or are coming down from the false high of sin, we feel that we are the worst of sinners, knowing better what we ought to do but still doing it. This can lead not just to proper repentance and confession, but sometimes to a sense of worthlessness and self-recrimination. Who are we to deserve God’s love? Why would God want me, of all people?

This is why it is important to stress that God cares for us at every point in our lives. Even if we feel we are not worthy of forgiveness, “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners—of whom I am the foremost.” It is “for that very reason,” Paul says, that “I received mercy, so that in me, as the foremost, Jesus Christ might display the utmost patience, making me an example to those who would come to believe in him for eternal life.” If the foremost sinner received mercy, you can, too. In fact, come and get it now.

God wants our repentance, not to demand obeisance but because we were created out of being for being, not out of nothingness for nothingness. God’s desire for us is for our true nature and destiny to be realized. We see this when the Israelites out of Egypt quickly turn from their saviour and the commandments given them to a golden calf. God tells Moses his wrath is burning “hot against them.” Moses, though, implores God and says, “Remember Abraham, Isaac, and Israel, your servants” and the promises of descendants and the land. In response, “the Lord changed his mind about the disaster that he planned to bring on his people.” As much as God hates sin, God loves us even more. This is why mercy, not punishment, is the gift that God offers us over and over.

This is not just an offer sitting on a back shelf somewhere. This offer was brought to us by God’s son, who came to seek us out and offer us the gift prepared for us. The set of so-called lost parables in Luke begins with an account of grumbling on the part of the religious experts of Jesus’ day because he was eating with tax collectors and sinners. It is in response to these complaints that Jesus tells three stories of a lost sheep, a lost coin and a lost son. They are so well known that we have to exercise care that their grit and groundedness in everyday life not get lost: God seeks out sinners in whatever muck he finds us in.

God rejoices over us when we are found. Listen to the endings of the three lost parables: “There will be more joy in heaven over one sinner who repents,” Jesus says, “than over ninety-nine righteous persons who need no repentance”; “There is joy in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner who repents”; “But we had to celebrate and rejoice, because this brother of yours was dead and has come to life; he was lost and has been found.”

As much as sin stalks us, when I look back at my life I see how many mercies and graces there have been, how God has been picking me up every time I fell and dusting me off. God keeps standing us up and telling us to turn away from sin and come home, for now is the time to share in God’s joy.

John W. Martens is a professor of theology at the University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, Minn.

Readings: Ex 32:7-14; Ps 51:3-19; 1 Tm 1: 12-17; Lk 15:1-32

Literacy Strategy Year 2 schools at MacKillop Centre.

Peter's Whereabouts for the next two weeks:

Upcoming Events:

No comments:

Post a Comment